At the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, Reactor No. 4 exploded spewing out a cloud of radioactive material that drifted into Russia, Belarus (which received 70% of the radiation fallout), and northern Europe.

For 10 days the plume of hot gases transported the radioactive elements - it was 200 times greater than the Hiroshima nuclear bomb.

At the blast site, 49 people were killed including workers and firefighters, however Greenpeace believe that as many as 93,000 in total will eventually die, particularly with cancers, as a result of exposure to high levels of radiation. This is still a highly contentious issue and we may never know the true number of deaths or associated illnesses.

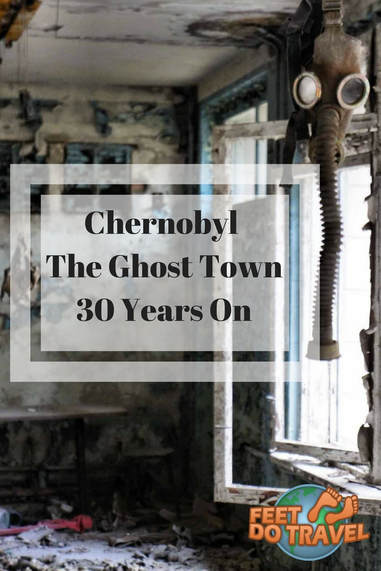

What about Chernobyl today, over 30 years on?

The fallout left the city as a ghost town and forced 43,000 Pripyat residents from their homes, never to return.

After the explosion, many inhabitants of Pripyat gathered on a railway bridge just outside of the city which provided a view of the nuclear power plant. They spoke of beautiful flames in all the colours of the rainbow (the burning graphite) and how the flames reached higher than the pillars of smoke. Sadly, what they didn’t know, was that the wind which swept over them carried with it a massive dose of radiation.

Of the people standing on the bridge that night, no one survived. It is now often referred to as the “bridge of death”.

In the time following the catastrophe, in nearby towns, a high number of babies were born with serious heart defects. This is so common that, even to this day, this serious defect is known as “Chernobyl Heart”.

High numbers of people of all ages were recorded to have developed thyroid cancer, not just in the surrounding areas of Pripyat but hundreds of miles away.

The Charity “Bridges to Belarus” warns that babies are still being born with serious deformities. One doctor reported “Before Chernobyl I'd never seen a child with cancer. Now it's common. I treat many more children now with heart defects and kidney damage”.

There are also many cases of animals giving birth to mutated young; human physical mutations such as tumours, extra and enlarged or distorted limbs. There are also a variety of disturbing mental disabilities.

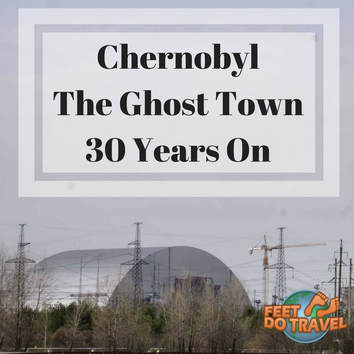

Despite the worst nuclear disaster in history, service and work resumed at the site only five months later. It wasn’t until 15 December 2000 that Chernobyl stopped producing electricity and was finally shut down. Only 3% of the plant’s radioactive material escaped, experts fear that if parts of the ageing reactor collapse, the remaining 97% could be spewed into the atmosphere.

30 years later I am left wondering, what does it look like? Has it recovered? Can the City move on?

I know of very few people who have been there, so when our friend Justin Murray visited a few weeks ago, I was fascinated to hear more. He kindly granted this interview with me.

Hi Justin, how are you today?

I'm doing well Angie! Enjoying the non-snowy April day in Berlin (it snowed 30cm back home in Canada last night!).

Oh wow! 30cm of snow in April back home? No wonder you are enjoying your day! Firstly, thank you for agreeing to take the time to talk to me, it’s much appreciated. My first question is for the readers, where are you in the world right now and what can you see outside your window?

Right now I'm living on the southern edge of Berlin...a part of the city that was not hit during the second world war...so I can see the old 1905 Rathaus (town hall) from my back deck.

So you currently live in Germany but you are from Canada, what brought you to Europe and how long have you been there?

While my job brought me to Europe in 2010, my love of the history here kept me in France for my first four years, and in Germany for the last two...and hopefully it will keep me here for a few more!

What has been your biggest challenge living in Europe?

The biggest challenge for me has been a surprise. I thought it was going to be language differences, but after travelling in many countries where English is not widely used, you learn workarounds and to rely on other forms of communication to get by (charades is my favourite). Luckily, English is quite often a secondary language spoken throughout Europe.

I'm an ExPat and as I don't go 'back home' after my travels, my biggest challenge has been missing the creature comforts that I'm used to having back in Canada. Things like television in my language, conversations about hockey games in the office kitchen, and food! I do enjoy all the new experiences living and travelling around Europe, but it's really important to be able to relax and recuperate some of the time as well!

I've covered a lot of France, Germany, western Poland, and the Czech Republic. I've hit the major tourist destinations in England, Scotland, Turkey, and the Balkans and at least the capitals in almost all the western European countries. I'm rather embarrassed to say that I've only been to Rome and Venice in Italy, and only Dublin in Ireland.

In most cases, especially in France and Germany, I've visited the more obscure sites because of my interest in medieval history. If I don't have a big trip planned for the coming weekend, I get out at least for the day to visit some ruined castle, converted abbey or a village's medieval centre.

You are definitely making the most of your time there aren’t you! And that’s exactly how it should be! And I love that if you can’t get away you visit a ruined castle, brilliant! So tell us, Chernobyl is an unusual place to visit, why did you choose it?

It was only recently that Chernobyl went on my 'travel list'. Last Halloween, I had visited an abandoned military hospital outside of Berlin and loved the experience. I took a few great photos from there which I thought captured the 'creepy' atmosphere perfectly. After that, I started looking around for similar sites nearby and throughout Europe. When I found Chernobyl, I knew that I had to go there!

Did you have any pre-conceived thoughts about what it would be like before you travelled there?

One of the first things I do before I plan to visit any historic/tourist site is to look-up photos of it. I've had more than one experience where the web-site described the building as a castle, when in fact the site had been destroyed and rebuilt so many times that it was now just a big house and all that remained from the original site was a stone outhouse in the back!

The photos taken of Chernobyl were incredible. All the pre-conceived notions I had came from these images.

How did you feel when you were there? What emotions did you experience?

Well, the tour started out with stops throughout the outskirts of the 30km Chernobyl 'exclusion zone'. There were quite a few settlements which were abandoned and completely overtaken by the forest. While they were sort of eerie, there really wasn't much there that I hadn't seen before (in terms of nature springing up around all these abandoned buildings).

There were lots of interesting sites in the outer Exclusion Zone, but it wasn't until we got to the inner 10km Exclusion zone that the nature of the site really hit home. In the inner Exclusion Zone there is the very surreal town of Pripyat and the sheer size of it was astonishing to me. There aren’t just four or five abandoned buildings but entire neighbourhoods and apartment blocks which are trapped in this forlorn state.

We had watched a documentary on our way to Chernobyl, so we knew quite a bit of the history before arriving. While the town of Pripyat looked like a movie set, it was hard to forget the details of the Chernobyl accident and how lives were effected and that really added to the creepy feel.

As for the reactor itself, that left me feeling completely different things. I felt a little sad for the men who died trying to contain the accident to save the lives of so many others. And looking at the gruesome concrete edifice, I also felt a little bit afraid but also a little relieved. If they hadn't sealed the radioactive leak and a second explosion had occurred, Europe would look much different right now and many more people would have lost their lives.

It seemed too large to be real. While walking down a main avenue, you could see down the side streets and this abandoned town and forest seemed to go on and on as far as the eye could see. Nothing had been rebuilt or was new. I kept expecting to come around the corner and find the Chernobyl McDonald’s or a local Tourist Office.

I should note though that there were some extremely obvious signs that people had been there. Most likely it was photographers trying to make the site a little creepier and had positioned dolls in window sills or on children’s beds. This most certainly made for some great photos, but were obviously not left behind like this during the evacuation.

In fact, a year after the town of Pripyat was evacuated, the people were permitted to go back and grab their essentials and other personal belongings. Whatever was recovered was then cleaned of any radiation it held before it was allowed to leave the site.

So there aren’t actually many signs of a mass evacuation remaining in the town. There are no breakfast tables still bearing tea and crumpets from 30 years ago.

Going back to what you said about seeing the reactor, it’s interesting that you felt afraid and relieved, I would never have thought of it like that so thank you for that insight. Now, you said that some settlements have been completely overtaken by the forest, I’m surprised to hear that nature is re-claiming the land considering what happened! Can you explain more of what you saw?

It really doesn’t take nature long to reclaim things when mankind isn’t there to control it which I have noticed in other abandoned sites I’ve visited. In Chernobyl’s case in particular, the radiation did not kill ‘all life’ surrounding the sites (although quite a bit of the nearby forest died within days of the accident). Forests (dead and alive) and structures that were built from wood all had to be torn down and buried after the accident. It was important to bury the wood and not burn it because wood absorbs radiation really well, it acts like a sponge and burning radiated wood just releases the radiation in to the atmosphere.

Another point of interest is that the Exclusion Zones have become a sort of accidental nature reserve. On our tour, we saw a herd of wild horses. There are also wolves, wild boar and, according to our tour guide, a bear or two in the area. Radiation is not good for these animals though, as some of them have tumours and decreased fertility. This shows that the effect human activity has on an area is far worse for some species than the possible effects of radiation.

I was going to mention the animals because I read a report recently that stated the lynx, roe deer and various other animal populations are thriving. Did that come across at all? Maybe the animals are out of sight and are thriving because they are away from humans. Or did you only hear and encounter those affected by radiation?

While all the animals are thriving, they are only thriving because there is no human intervention in their habitat. In fact, all species have been effected by the radiation, but whilst they are all affected, they aren’t all dying from the radiation. For example, the horses that I saw were all happy and running around etc, but the nature of radiation is that it’s invisible.

There are people that still live and work in the outer Exclusion Zone, but they are only allowed to stay there intermittently (I can’t recall the exact numbers, but I believe it was 4-days-on and 3-days-off or 15-days-on and 7-days-off…something like that).

The problem is that the animals never leave. While they’ll never breed horrible mutations like 2-headed-wolves or winged-horses, it’s their insides, their internal organs, which are effected.

Well, there is a statue built to remember the firemen who first ran in to attempt to contain the fires. But other than that, no, there is no grand museum or ‘learning centre’ in the area. That was something that surprised me for sure. I asked our tour guide if this was a protected site by the government or by UNESCO. He responded by saying that for the Ukrainian people, this is not a historic site that needs to be preserved. If people could move back in safely and live there, they would. If they could tear down the buildings and use the materials elsewhere to rebuild homes, they would. In fact, things like metal can be cleaned of radiation and sold for scrap.

The government has already gone in and pulled out any large amounts of metal from the Exclusion Zones and after cleaning it, they have re-purposed it to be used throughout the country (which explains why there are almost no vehicles that were left behind still in the zone).

This place is definitely not set-up for the mainstream tourists. You won’t find any shops selling t-shirts or fridge magnets. There are no happy residents waiting to get their photos taken with you. In fact, we were not allowed to take any photos of the guards at the various road blocks along the way. And, at the nuclear plant itself, we were not allowed to take any photos of it except from one small and specific mound. The tour guide mentioned that it is forbidden to take photos of any nuclear plants anywhere in the world and Chernobyl, after being decommissioned, is no exception.

So what are the people like?

The only people we interacted with were at a small diner in the actual city of Chernobyl (further away from the Nuclear plant than the town of Pripyat). They weren’t very talkative at all, but as we were a tour, we were all speaking with each other. We never saw anyone outside of the town of Chernobyl except at one point, in Pripyat, when we came across another tour. Other than that, we were alone.

Did you have an opportunity to speak with anyone about the disaster? Did anyone mention what it is like to live with an invisible radioactive enemy? Was there an opportunity to ask anyone if they were around at the time of the disaster and if they experienced what it was like to be there? If you did, was it as the reports of the day suggested “that the skies darkened as though the feeling of an apocalypse was happening”?

No, we didn’t hear any stories from the locals. But, to answer your question about the ‘feeling of apocalypse’, in the documentary shown in the van on the way from Kiev, no one outside of the nuclear plant knew that anything had happened. The people in Pripyat went about their lives as normal for an entire half day before the military showed up. And even then, the military were just performing tests throughout the afternoon. It was only when the tests showed radiation levels were getting worse and worse that they finally started the evacuation, and this was described as completely calm and relaxed.

One survivor who was interviewed said she expected to be able to return in a day or two to resume life as usual. As far as I can tell, the true terror about the situation was kept secret from the population. Only the scientists and the army realized how much trouble they were in.

I booked everything through a UK tour company named Lupine Travel (www.lupinetravel.co.uk) who seem to specialize in “interesting destinations”, Iran and North Korea are examples of other places they visit. I actually did some quick research about the tour beforehand, which is lucky, because at the various official road stops throughout both Exclusion Zones, they need your passport details before you can enter. The tour company I used sent them all of my passport information beforehand.

I would definitely recommend you do some research about the various tour companies. The first two websites I viewed looked great and very tourist-friendly, but then I found a review that opened my eyes to the possible problems. I won’t mention which tour operators are fake or shady as this is purely hearsay. Just remember that there are no “certified” tour companies that operate in Chernobyl.

Do you feel this is a place that should be visited or left alone?

That’s a tough question to answer. On my tour, there was a rather rude guy who kept asking obnoxious questions, although, to be fair, I could see his point. At the beginning of the tour he kept asking when we were going to get to something more interesting because the over-grown houses and municipal buildings in the outer Exclusion Zone were nothing he hadn’t seen before. I didn’t mind at all, because the documentary we had watched whilst travelling from Kiev to Chernobyl really got me thinking. It stirred up a great deal of imaginative notions through my entire trip.

I definitely think people should visit, but would strongly recommend that some research is carried out regarding the disaster prior to their trip, purely to bring a historical reality to the site that they are visiting.

Also note: when we were there, there were very few rules. The rules that did exist, seemed to be ignored some of the time. For example, we were not allowed to go in to the buildings (for obvious safety reasons in some cases), but as there was no one there enforcing the rules, we snuk into a few which really was amazing.

As more tourists visit, as time goes on, more rules will be added and there will be more people to enforce these rules. Therefore, if you are interested in visiting, try to get there sooner rather than later!

When you left the country, what were your lasting thoughts/impressions?

During the documentary, they reported what happened right after the first explosion occurred at the plant. They said that it was very likely that if left unchecked, a second explosion would happen. The scientists theorized that a second explosion would send out even more nuclear fallout which would affect most of Europe in ways similar to the Exclusion Zones.

It’s good to know that nuclear reactors these days are built with containment units so this situation will not be possible in the future. And yet, it scares me to think that a catastrophe of that sort and magnitude was ever a real possibility.

Justin, thank you, I think we were all gripped and intrigued by your account of what happened during you time there, and I can really get a sense of what it must feel like to visit through your descriptions. Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me and thank you for sharing your story with us all!

If you have been affected by this interview and want to help any children or people of Chernobyl, listed below are various charities you can support.

Chernobyl International

Bridges To Belarus

American Belarussian Relief Organization (ABRO)

Halloween in Tranyslvania

5 Must See Attractions in Romania

6 Reasons Why You Should Visit Croatia

Captivating Cyprus

6 Best Places to Visit in Greece

Cheese Rolling Anyone?

My London Bucket List

A Quirky Afternoon in Bristol

The Historic City of Nottingham

10 Breathtaking Sights in Iceland

ICEHOTEL and a Wedding Dress

Surviving Oktoberfest When You Don't Drink Beer

7 Things to do in Amsterdam (Instead of Red Lights and Coffee Shops)

If you like this post, please Pin & Share it!